You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Medical School’ category.

As a family physician, one of the more fun conditions for me to care for is pregnancy, childbirth, and the well child checkups that follow.

I meet women at the start of their pregnancies and learn a little about their lives beyond their pregnant “condition.” I see them every month for a long stretch, meeting mothers, mothers-in-law, friends, and husbands along the way. As things progress I see them every two weeks, and then weekly.

By the time the weekly visits occur I find out what my patients are made of – and they get to know me, as well. Mama is very pregnant, and my job is to convince her that every day inside, even past the mythical due date, is good for the baby. I then get to witness the miracle of childbirth (and occasionally play a larger role).

In my practice, mother and baby come back to visit weekly, monthly, and then annually as the children reach toddlerhood. We continue to have conversations around the new family and the transitions up until the age of three. After that, if the child is well, we are limited to an annual “Hi, how are you doing?” For the most part, they are moving on with their lives as a young family and fortunately do not need my help. In the words of the Lone Ranger,”My work here is done.”

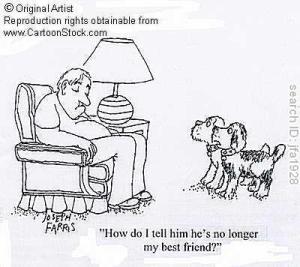

However, it isn’t quite as easy as that. Doctoring is a funny gig when it comes to personal relationships. I’m sure there are others just as funny, dentistry probably being one. I see these folks back for a visit after a couple of years, or at a community activity, or elsewhere in Mobile and surrounds, and the mothers will proudly say to their (very embarrassed) twelve-year-old, “There’s the first person who ever saw you.” We’ll make some small talk — what do you say to a twelve year old after nine years? — and typically the mother will ask about my family and my kids.

Because, as it turns out, while they were sharing a part of their story with me, I was sharing a little of my story with them. I used my children as examples for feeding and discipline problem-solving, as both good and bad examples. I discussed my wife’s meal-time solutions for feeding grown-ups and kids at the same table. In other words, I shared with them as they were sharing with me. A little piece of my version of how we put our kids to bed has entered into the bedtime strategy of many of the families that I have cared for. If “Good Night Moon” did become a successful part of their ritual, I hope they think of Dr. Perkins in a really good way (after the toddler is actually asleep, of course).

I don’t get to care for a lot of young families any more, given my other duties, but I do still see folks that I have cared for over the last twenty years, people with whom I have shared family anecdotes in this manner in the hope of leading them to better health.

It has been six months since my wife’s death. Many of my patients, coming in for a variety of reasons, or running into me around Mobile, have wanted me to know that they are here for me just as I, and our family, and some of my

wife’s child-rearing strategies, were there for them. It has meant a great deal to me.

Through pestilence, hurricanes, and conflagrations the people continued to sing. They sang through the long oppressive years of conquering the swampland and fortifying the town against the ever threatening Mississippi. They are singing today. An irrepressible joie de vivre maintains the unbroken thread of music through the air. Yet, on occasion, if you ask an overburdened citizen why he is singing so gaily, he will give the time-honored reason, “Why to keep from crying, of course!

It is a month today since Danielle’s death. I had already planned to go to New Orleans for my 30th medical school reunion by myself prior to her death, as she was to be playing Amanda this weekend in a local production of Glass Menagerie. The play is set in St Louis. Tennessee Williams, the writer of the play, once said “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” Clearly, he set it in St Louis for a reason. Danielle was a New Orleans native, and she understood those reasons.

I lived in the Faubourg Marigny (a neighborhood just outside of the French Quarter) while I was in medical school. After we married, Danielle and I moved to the Irish Channel, a neighborhood that is quite gentrified now but was much less so 34 years ago. For those of you who know New Orleans, we were one block off Magazine and spent many afternoons there walking and window shopping.

After moving to Mobile we found ourselves in New Orleans many times a year. We would go to Danielle’s mother’s house and, after a suitable time, we would make an excuse and go to Magazine Street. The children had valuable grandparent bonding time, and we had New Orleans time. This became less frequent as the children grew older. After Katrina, both of our immediate families left south Louisiana and so our visits were limited to special occasions. We still made it about three or four times a year, however, enjoying many delicious meals with our friends and extended family, and spending time window shopping on Magazine.

This weekend, I played hooky for much of my 30th reunion. Staying with friends of ours in their uptown home, we drank wine and remembered the old times. New Orleans being New Orleans, we went to the Boogaloo Festival and heard the Lost Bayou Ramblers. We spent time among the thirty-somethings, watching them frolic in the old (not very clean looking) Bayou St. John canal. It was hot. All in all, a very New Orleans experience.

At the reunion events I did attend, word quickly spread about my wife’s death. Many came up to me and offered condolences. Most of them only knew Danielle peripherally, so I didn’t have many in-depth conversations. “So sorry for your loss,” they would say. “Thank you for your kind words,” I would mumble back. Since many of these old acquaintances are no longer married to the spouse they boasted in medical school, discussions of marriage and relationships are typically avoided at these reunions altogether. One of the more awkward moments, in fact, was when we toasted to those who helped us get where we are and the person next to me said: “Wait, am I toasting my EX-wives?”

I guess my loss really hit me when I was driving down Magazine Street on my way out of town. I saw all the familiar buildings that were built before we were born and will likely be there after our deaths, and I realized that my loss is not just the Danielle of today. My loss is the life we built together and the life we expected to continue to share. That loss includes our shared experiences and memories. Our stories. Our jokes. I realized that I had lost not only Danielle but our shared New Orleans.

“So sorry for your loss.” For those who knew us, it is a shared loss and I am sorry for your loss as well. For others, I really do appreciate the sentiment, even though I may respond less than enthusiastically at times.

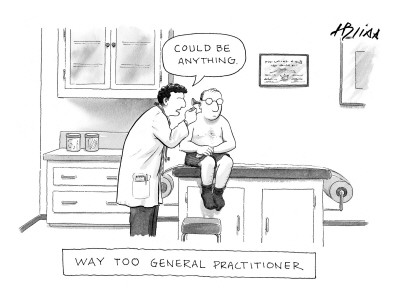

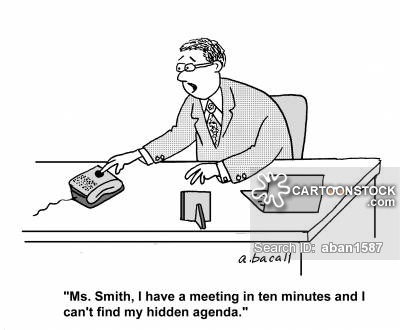

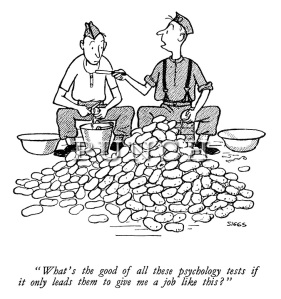

Student overheard on interview tour: Boy, I really put one over on Perkins. I told him I wanted to be a Primary Care doctor…and he bought it. I’m sure to get in now.

What do we look for in medical students? No matter what, we want our physicians to be smart. The selection process is designed to weed out “not-smart” people. Unfortunately, we can only measure smart in a couple of different ways (grades and MCAT scores), ways that tend to benefit the wealthy (60% of medical students are from the upper quintile of income) and non-minority folks (14% of medical students are from underrepresented minorities compared to almost 25% of the population).

Is there another criteria we should use for selecting medical students? Altruism in medicine is best described in the words of this medical student:

So, for me, I see it as always putting yourself behind the person that you’re with. So the patient comes first, no matter what. If it means spending extra time past normal office hours to stay, if it means going out of your way for somebody, if it means sacrificing something for yourself, I think that’s what it is. First and foremost, you’re taking care of the patient.

Can we assess this in a medical school application? Unfortunately, not very well and not in a reproducible manner. We tend to put value on things we can quantify, so an MCAT equivalent of 37 (99th percentile) would attract the attention of the admissions committee much quicker than a prolonged experience at a soup kitchen. As one of my fellow admissions committee members said, “You can’t assay for the Give A Crap gene,” but you sure want your doctors to have it. The MCAT predicts how well the student will perform on tests but has no bearing on how good of a physician they will be. The soup kitchen experience may take away some grade and MCAT points, but give me that doctor-to-be every time.

Another marker is not the number of experiences but the intensity and commitment shown. The best people I have interviewed have been folks who have decided on medicine after several years of Teach For America or similar life experience. These folks tend to be better able to communicate with patients and, not coincidentally, tend to seek careers in primary care.

The best way to assess this, so they say, is through the interview process. As an interviewer, I will look at the student’s activities and query them regarding each of the things listed. Although not focused on primary care, I try to focus on whether or not the person has the GAC gene. To be honest, if in my opinion they don’t, I am not certain enough on my ability to assess to sabotage the application. If they do, I try to recruit them into our school. If not, I try to sell them on the other allopathic medical school in the state.

Charity Hospital in New Orleans was an incredible place for learning clinical medicine in the 1980s, a veritable clinical playground. As a third year medical student I was required to do difficult blood draws, put in central lines, and other tasks after seeing someone else do one (the phrase is “see one, do one, teach one”). In addition, I was called upon to write orders for antibiotics and do other “doctor” things which taught me responsibility, with my role increasing as I become more experienced. It was, however, a playground that was largely unsupervised.To say that supervision was limited was, well, charitable. We saw the attendings maybe once a week in the clinical wards. The residents were overwhelmed, leaving much of the work and the decision making to the medical students. As a student I grew up fast but often acted with little clinical seasoning and limited information.

Charity Hospital in New Orleans was an incredible place for learning clinical medicine in the 1980s, a veritable clinical playground. As a third year medical student I was required to do difficult blood draws, put in central lines, and other tasks after seeing someone else do one (the phrase is “see one, do one, teach one”). In addition, I was called upon to write orders for antibiotics and do other “doctor” things which taught me responsibility, with my role increasing as I become more experienced. It was, however, a playground that was largely unsupervised.To say that supervision was limited was, well, charitable. We saw the attendings maybe once a week in the clinical wards. The residents were overwhelmed, leaving much of the work and the decision making to the medical students. As a student I grew up fast but often acted with little clinical seasoning and limited information.

Mostly what I remember is being scared that I would miss something. We had lectures in every clinical specialty but I remember them as being esoteric. at best. The Starling curve, while unquestionably amazing and unfailingly covered once a week, had little to do with what the Lasix dose should be in heart failure (for this particular drug the “Fat Man’s law” was much more useful). When I discovered the lectures were less useful than a work of fiction, I really panicked.

What did I use? For Internal Medicine, there were two great books. Harrison’s was written by a gentleman named Tinsley Harrison who had by that time made his way to UAB. Cecil’s was written by another guy (named Cecil, I believe). They covered the same material and were each over 1000 pages in length. I had classmates that read them both, in case there were discrepancies. The Washington Manual was written by some residents at Washington University (St Louis). My attendings looked down on it because it was lacking the academic rigor of Harrison’s or Cecil’s. I found it very useful at 0:darkthirty with a sick patient and not much time. If we had time, we went to the library. There was a multi-volume set, the Index Medicus, where one could look up a factoid using key words and track it to the source.

In addition, we used each other. We would ask each other “Hey, what do you think about…” and reassure ourselves that whatever course we decided on was the best one. We would then get the opportunity to defend ourselves in the cold light of day, always being asked for our source of information. We never claimed our colleagues as the source.

Which brings us to yesterday. I was the attending (Attendings now round every day) and their was a question about optimum antibiotic selection for a neonate with a fever. No textbooks. No manuals. Cellphones and tablets came out, databases were consulted (along with Up To Date) and within 3 minutes an evidence based answer was obtained (in fact, I won the mad google prize by getting to it in 3 clicks). Patient received optimum treatment less than 3 minutes after the treatment course was decided.

From the literature, it was clear that the Cecil’s/Harrison’s/Index Medicus skills used in residency did not move with the physician to private practice but asking a colleagues (or drug reps) opinion did. I am hopeful that mad googling skills will.

Discussion in medical school admissions committee:

Colleague: So I asked him “just why do you think you want to be a doctor” and he said, “Oh, you know, I like science, want to help people , like to problem solve.”

Me: I just learned about a new term called “the consent agenda.” In a meeting, if there is stuff everyone agrees on, you put it on the agenda as “consent items.” Then, with no discussion it can pass and you can move on to discussing something germane. I propose we notify all students that love of science, helping people, and problem solving are consent items. Then, we need to find out, how does this person know they REALLY want to be a doctor?

I just learned about this web site called DOC. DOC stands for “Drop Out Club” and it exists to help people transition from clinical medicine into a non-clinical arena such as management or sales. On their web site they say that the “name reflects the sentiment at our original gathering that no clear support systems existed for the paths we were pursuing.”

The site has about 10,000 members, although some may be lurkers like me. The forum at the site is full of folks who feel like they have made a terrible mistake with their lives and are looking for a way out. Many are in residency with statements like “I look around and can’t see myself doing this for the rest of my life” predominating.

Physician career dissatisfaction is a real problem. About 400 physicians commit suicide each year. Suicide is the number 2 cause of death in medical students (following accidents, some of which are also likely suicide). This is thought to be a consequence of underdiagnosed depression, almost certainly made worse by a rapid and monumental debt accumulation. In addition, I will concede that a love of science, a desire to help people, and a joy of problem solving are all good attributes. Unfortunately, they are not sufficient to combat an inchoate fear that you are 5 years and $300,000 into a terrible, terrible mistake. And it starts early, also:

A study of all medical students in the United States found that about 49.6% of medical students met the criteria for burn out and 51.3% for depression. Trust me—it’s not all from studying, but from being treated like crap, feeling like we can never make a mistake or ask for help and wondering if anything we do will help to change the status quo or are we just cogs in a wheel trying to crush us.

Approximately 15 years ago, Don Berwick outlined the triple aim for improving healthcare in this country – enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs. Tom Bodenheimer recently outlined a fourth aim – improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff. He identifies the following as some of six things we can do in primary care to keep our colleagues engaged and off the DOC website:

-

Reduce the burden on the physician through team documentation: An encouraging trend I have seen among pre-med students is their being engaged as scribes. This way they get to learn what it is really like to be a physician by being a part of the team and the physician gets to go home without having to do two hours worth of charting after dinner.

-

Expand roles allowing nurses and medical assistants to assume responsibility for preventive care and chronic care health coaching under physician-written standing orders. Things that are automated should happen automatically with the physician not being a barrier to good preventive care. We need to model this for students

-

Co-locate teams so that physicians work in the same space as their team members; this has been shown to increase efficiency and save 30 minutes of physician time per day. We have gotten rid of the office in our practice. The physician work space is a shared space where interaction can occur. It is really important to level the field.

-

To avoid shifting burnout from physicians to practice staff, ensure that staff who assume new responsibilities are well-trained and understand that they are contributing to the health of their patients and that unnecessary work is reengineered out of the practice. This holds true for student members of the team as well. They need to understand their role in care delivery as part of the stress of being a student is constantly being thrown into a new environment.

In short, what we as educators need to do is make sure students understand what they are getting themselves into and make sure they have the tools necessary to do the tasks they are assigned. What students need to do is look away from the books and understand that this is not about science or helping people but is about acquiring the skills to enter into a very difficult profession. While interviewing a residency candidate for our residency it came out that she had been to cosmetology school and had cut hair at Walmart for 2 years. I asked her what the best thing she had learned from that experience was, and she said “When people sit down in that chair and say ‘do whatever you want,’ they don’t mean it.” I suspect she won’t burn out.

I have to remember that I’m an officer and when I give a Marine an order they will obey no matter what. When I use the tonometer and say “don’t blink” I had better remember to follow up with “blink” before they get dry eyes.

Conversation with a Navy Optometrist

I remember fondly my time being a doctor to the Marines. Wet behind the ears, eager to hone my craft, suddenly given superhuman abilities such that with only an internship I could function independently in a remote setting…oh, wait, that last part didn’t happen. Fortunately there was, on the base with me, a wizened old doc (I think his name was Wenzel) who had practiced in rural Kentucky prior to going back and studying pediatrics. His counsel was always wise and when distilled down often ended up being “When in doubt, turf it out.”

We were at a fairly busy ambulatory clinic and urgent care center in Kaneohe, Hawaii. All of us took call. I remember making multiple trips to the civilian hospitals to transport patients. The active duty dependent and military retiree patients had to pay quite a bit out-of-pocket if they used the civilian facilities without consulting us first. We used to get folks driving PAST the civilian hospital to come to our ambulatory dispensary having heart attacks (I can remember one dying on the H-3 while in the car, wife driving 80 miles an hour) and respiratory arrests (one of the most harrowing ambulance rides of my life, ever) in addition to the assorted 21-year-old Marines who never failed to learn the lesson that alcohol renders no one invincible. The lessons I learned there about the limits of an ambulatory practice setting, the triage and transport of sick people, as well as the health risks folks will take as they try to save a buck, have stayed with me for 25 years.

I also learned some very concrete lessons on practice organization and care delivery. First, we had a very robust quality assurance program and worked hard to create a culture of quality and safety before it was fashionable. Second, against the wishes of the base commanding officer who wanted to have “his own hospital,” any attempt to be who we were not (a small ambulatory presence designed to get folks the care they need when they need it) was resisted by folks above my pay grade. Third, the Navy was experimenting with nurses in charge of practices such as this and I was extremely fortunate to work with several very good Nurse Corps OICs and learned to work as a member of a care team.

The military is a unique practice environment. The emphasis on readiness as well as wellness provides lessons for all of us in healthcare. Unfortunately, military medicine may be in trouble. The remote locations, providers who may not be invested with tours of only 3 to 5 years, and inexperienced physicians who are moved rapidly up in rank based on medical training apparently has led to problems. The New York Times has recently published a story highlighting the downside that is worth a read. I was most struck by the quality and safety problems highlighted in the article. Physicians are apparently being placed in small hospitals with skills ill-suited for the location and/or patient population and attempting to provide care comparable to what they learned in their training. In addition, data aggregation techniques now used in the civilian world to assess quality and improve care are not in common use in the military hospitals. Leadership positions are being given to physicians who have a high rank by virtue of their residency training but limited real world or even military experience. The military is not entirely to blame. When they try to consolidate hospitals or provide care in a different fashion they are obstructed by the community, who uses their congressperson to keep the jobs local.

Our troops and their families as well as those who have retired from active duty have the expectation of high quality and safe healthcare, as does the general public. We need to equip all physicians with the skills necessary to practice in the environment in which they find themselves. Surgeons in isolated areas need to focus on doing small procedures well and leave the complex cases for hospitals with teams to provide care, whether on a military base or in rural Alabama. We need to teach how to assess and incorporate meaningful quality and safety practices starting at day one of medical school and not assume competency by virtue of a residency training certificate. The Milestone project seems to be a good start at making sure this happens at the residency level. Lastly, we need to teach leadership. Physicians are expected to be leaders. It’s time we give them the tools to do it.

I just finished reading The Celestial Society, a biography of George Burch written by his daughter Vivian. I knew him as an older attending who seemed oddly out of touch with students. I now know that he was a beaten, sick man at the time I had contact with him. I also found out that he never deviated from his core belief that what medical schools needed to do was train good generalist physicians and develop tools to allow these generalists to become better doctors. He was Chairman of Medicine at Tulane for 30 years, forced out in the 1970s when he opposed the creation of a practice plan to capture faculty patient care revenues. The dean and the chancellor both felt that without the ability to harness this revenue source, Tulane would be forced to shut down.

I just finished reading The Celestial Society, a biography of George Burch written by his daughter Vivian. I knew him as an older attending who seemed oddly out of touch with students. I now know that he was a beaten, sick man at the time I had contact with him. I also found out that he never deviated from his core belief that what medical schools needed to do was train good generalist physicians and develop tools to allow these generalists to become better doctors. He was Chairman of Medicine at Tulane for 30 years, forced out in the 1970s when he opposed the creation of a practice plan to capture faculty patient care revenues. The dean and the chancellor both felt that without the ability to harness this revenue source, Tulane would be forced to shut down.

It is amazing how much medicine changed in the 40 years of Dr Burch’s career. Dr Burch’s entire career was at Tulane and spanned from the 1920s to the mid 1980s. When he started the EKG “machine” was a string galvanometer and was only done on selected patients. He was instrumental in describing variants of EKGs, wrote the first book on interpretation which made the technology available to all clinicians and developed the circuitry which allowed all 12 leads to be measured simultaneously. All the while he was on faculty at Tulane, making very little money when compared to his private practice colleagues and caring for poor patients at Charity Hospital. To him the academic “life of the mind” and the noble activity of caring for the poor sick should have been rewarded by society. The building of a University Hospital with the corresponding contractually obligated faculty sounded the death knell for this type of medical practice.

The conflict at Tulane was the result of Dr Burch’s stature in the world of Cardiology and the perception that his belief regarding cardiac surgery were holding up progress. He believed that outcomes were terrible. His perception was that patients were more likely to die from the surgery than the disease, a belief grounded in observation but since surgeons kept no data not measurable. He believed that surgeons were uneven at best (again, unmeasurable) and in reality it was the post-surgical care that mattered the most. He abhorred the “chance to cut is a chance to cure” mentality and in his clinical experience many people would be better served to have nothing done than to subject themselves to angioplasty or surgery. Tulane wanted him to refer his patients exclusively to Tulane surgeons and likely expected a larger number of patients to be referred, conditions to which he was unwilling to agree. Medicine was moving into an entrepreneurial direction and Dr Burch was being left behind.

Dr Burch died in 1986. Tulane continues to thrive (at least according to the alumni magazine) despite not being in Charity Hospital at all. Many of his beliefs regarding invasive cardiology have been affirmed. Meanwhile, the article on colonoscopy in today’s New York Times, illustrates the cost we have paid for dismissing Dr Burch’s warnings regarding our abandonment of the generalist physician model and embrace of the entrepreneurial model of medicine.

The high price paid for colonoscopies mostly results not from top-notch patient care, according to interviews with health care experts and economists, but from business plans seeking to maximize revenue; haggling between hospitals and insurers that have no relation to the actual costs of performing the procedure; and lobbying, marketing and turf battles among specialists that increase patient fees….

When popularized in the 1980s, outpatient surgical centers were hailed as a cost-saving innovation because they cut down on expensive hospital stays for minor operations likeknee arthroscopy. But the cost savings have been offset as procedures once done in a doctor’s office have filled up the centers, and bills have multiplied.

It is a lucrative migration. The Long Island center was set up with the help of a company based in Pennsylvania called Physicians Endoscopy. On its Web site, the business tells prospective physician partners that they can look forward to “distributions averaging over $1.4 million a year to all owners,” “typically 100 percent return on capital investment within 18 months” and “a return on investment of 500 percent to 2,000 percent over the initial seven years.”

To quote Chairman George, “I’m not antisurgery, I’m pro-patient.”

When I was in the Navy, we used to have an expression when the paperwork burden would get too great, something to the effect of “What we need is a good war.” The belief was that war had a cleansing effect on the bureaucracy, streamlining processes and making things measurably better. I suspect, after 10 years of readiness, my former colleagues are no longer so convinced of that.

When I was in the Navy, we used to have an expression when the paperwork burden would get too great, something to the effect of “What we need is a good war.” The belief was that war had a cleansing effect on the bureaucracy, streamlining processes and making things measurably better. I suspect, after 10 years of readiness, my former colleagues are no longer so convinced of that.

I was reminiscing about my military service in part because I was loaned a copy of Unbroken – A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. Well worth a read, it tells the well researched and improbable story of survival of the impossible by Louie Zamperini. My first thought, upon finishing it, was that World War II was fought by folks my son’s age. I cannot see him piloting a bomber, and I suspect when World War II started many parents felt the same as well.

Medicine is using the aviation industry as a standard to move towards regarding process improvement and safety. My other thought was about how the aviation industry became so focused on safety. This book makes me think that our World War II experiences probably played a large role in this evolution. When the war started, training accidents were common. In fact, for every one combat aircraft casualty, there were 6 training casualties. Zamperini and other survived their training in part because they were excellent problem solvers in potentially lethal situations. The non-combat risks included the hardware itself, the weather, support structures including landing facilities, the risk of human error, and the risks of navigation.

To reduce this loss of aircraft and people (as many as 1 in 4 aircrew died in World War II), the entire way of thinking about flight had to be changed. It took the national needs, tremendous human loss, and an understanding that system change was vital to our survival to bring about that change in the military. Louie was an early casualty (his poorly equipped and maintained plane crashed in the Pacific on a search and rescue mission) and spent much of the later war in the POW camps in Japan so he didn’t experience this system change. Many would say it was then the military pilots and crew transferring what they learned into civilian aviation that improved civilian air travel as well.

The book reaffirms the horror of war, in particular the pacific theater. I know that as a trade-off, safe air travel is not nearly enough to compensate for the losses of my parents generation. We consider losses from death but almost worse were the emotional trauma that survivors have faced. Zamparini was quoted as saying that if he know he would have to relive his experiences he would kill himself. Now in his mid 90s, he is an amazing individual. His story is one of personal triumph when he was failed by the system. What we have begun to learn in medicine is the need to minimize personal heroism and maximize the triumph of the system.

When Laennec invented the stethoscope in 1816 and physicians no longer had to put their ear to the patient’s breast, health care delivery changed. Asepsis, effective treatments for syphilis, and other breakthroughs soon followed. By 1910, medical education needed to move on as well.

When Laennec invented the stethoscope in 1816 and physicians no longer had to put their ear to the patient’s breast, health care delivery changed. Asepsis, effective treatments for syphilis, and other breakthroughs soon followed. By 1910, medical education needed to move on as well.

Scientific breakthroughs had altered the values held by the public and the medical profession: clinical and laboratory research had exposed the irrationality of “heroic” treatments (such as blistering, bleeding, and purging) and had proven the therapeutic efficacy and rational scientific basis of modern practices, such as antiseptic surgery, vaccination, and public sanitation. Most of the public and virtually all physicians now believed in the superiority of scientific medicine

Medical education underwent a transformation that lasted until very recently. The first two years were heavily influenced by science and the medical students were taught, not by physicians but by “basic scientists” whose training was in anatomy, histology, biochemistry, physiology, and other “hard sciences.” Students were then allowed access to patients, with whom they would presumably spend the rest of their lives.

Does it work today? The LCME, the board that governs the majority of the medical schools in this country, looked at just that (report found here). The good news: Doctors trained under this system are knowledgeable and technically proficient in providing care for acute disease; they wish to do what is best for their patients; and patients respect them as credible sources of information.

The bad news? Again to paraphrase from the report:

- Physicians are not prepared to evaluate the care they provide in their own practices and to use the results to improve patient safety and the quality of care provided.

- Physicians are generally not prepared to be advocates for patients on issues related to social justice (for example, elimination of health care disparities, access to care) and to be citizen leaders inside and outside of the medical profession.

- Physicians often lose altruism and qualities of caring as they proceed through training and enter the practice environment.

- Because of their training, physicians find it difficult to deal with the inevitable uncertainty arising from incomplete or conflicting information. Additionally, they are not typically prepared to convey their uncertainty when interacting with patients and colleagues.

- Many physicians are not prepared to utilize information technology to assist in information acquisition and management.

- Physicians are trained to be autonomous. This can be a barrier to providing patient-centered care, where patient values and desires are an integral part of shared decision-making. The expectation of autonomy diminishes the ability of physicians to act as team players with other physicians and other health professionals.

- Physicians are not prepared to participate in ethical and political discussions about the allocation of health care resources, which are not limitless.

- Graduates do not acquire skills in cultural competence/awareness and to recognize that some patients may have health literacy issues.

So, what’s the problem, you say? Teach the science and teach the humanism (like having chocolate and peanut butter together). The limiting factor is time and the explosion of factoids that are considered “vital” for a physician to know. Or, to put it another way by someone who thinks things are just fine:

Increasing emphasis on apprenticeship-based education and increased focus on the non-medical knowledge competencies inevitably will be at the expense of rigorous training in the basic sciences if the existing number of hours available for teaching are maintained.

In addition, the teaching of the lacking humanism skills will require another type of medical education specialist, one much more skilled in communication than in versed in scientific discovery. The basic scientist may be on the way out when it comes to educating physicians. The article referenced above is a plea for not allowing the science education of our nascent physicians to be diminished. The author expresses concern that though care may improve and patients may be more satisfied, we as a profession and our society may be poorer as a result. I would argue the system begun in the 1910s has left us with an expensive and not very effective care delivery platform and is destined for failure. I would also argue that we must improve the value (cost, quality, and efficiency) of our clinical care, a challenge that will require all physicians to be versed in the skills identified above as lacking. We need to teach smarter. If we do not, we may be seen as upholding our scientific standards as we bankrupt our society.